The Chapulín Colorado

El Eternauta (tv series)

El Eternauta, the Argentine series directed by Bruno Stagnaro and based on the legendary graphic novel by Héctor Germán Oesterheld and Francisco Solano López, has brought one of the most influential Spanish-language works of science fiction to the screen with both technical ambition and deep respect for its original spirit. At its core, the series embraces the concept of the “collective hero” —a foundational idea in the story and one that Stagnaro champions as a political and cultural stance against individualism.

From the outset, El Eternauta declares that survival is not an individual act but a collective endeavor. This theme permeates the narrative and is mirrored in the collaborative nature of the production itself. The plot unfolds in a Buenos Aires gripped by a deadly, mysterious snowfall that wipes out much of the population. As the survivors begin to understand they are facing an alien invasion, they realize that unity is their only path forward. To preserve the urgency and social resonance of the original story, Stagnaro chose to set the adaptation in the present day.

Bringing El Eternauta to life also required cutting-edge technology. To create its dystopian vision of Buenos Aires, the team turned to Unreal Engine —a software platform originally designed for video games and now widely adopted in film and television. Using this tool, real-world locations throughout the city were digitally scanned and reimagined as detailed three-dimensional environments.

These virtual sets were then projected onto massive LED walls during filming, a process known as virtual production. This technique allowed actors —including Darín and César Troncoso— to perform within immersive digital landscapes in real time. More than just a visual upgrade, this approach gave the creative team tighter control over mood and tone, transforming Buenos Aires into a fully integrated character within the story rather than a passive backdrop.

The series was the result of an unprecedented collaborative effort among several Argentine studios — including Control Studio, Many Worlds, Beat, Malditomaus, and Bitt Animation— alongside international partners. Virtual production involved months of research, 3D modeling, texture design, on-set coordination, and over a year of meticulous post-production, during which every shot was reviewed alongside Stagnaro to fine-tune its visual storytelling.

Beyond the technical sophistication, Stagnaro sees El Eternauta as an opportunity to build an Argentine heroic mythology —one rooted in local identity yet capable of resonating globally. Rather than softening cultural references to appeal to an international audience, the series proudly amplifies them. It’s a deliberate choice grounded in the belief that authenticity, not universality, is what fosters true connection across borders.

Nearly seventy years after its original publication, El Eternauta remains a story of resistance, solidarity, and memory. Oesterheld’s visionary work begins a new chapter —where art, technology, and collective spirit come together to once again remind us that in the face of catastrophe, no one is saved alone.

Planeta Inquietante

Cosmic Magazine

Calien

Calien is a short novel that delivers a keen reflection on the human condition in a world where scientific progress and moral decline go hand in hand. Published in 2009 by Diego Darío López Mera, it stands as one of the most original efforts to fuse science fiction with Colombia's cultural and social landscape —particularly that of the city of Cali.

At its core, the story follows a family in pursuit of the elixir of immortality, only to become entangled in a web of conspiracy, betrayal, and encounters with non-human intelligences. Rather than a path to salvation, immortality emerges as a symbol of inner decay. In Calien, the strange inhabits the everyday, and the alien reveals itself to be none other than ourselves.

López Mera's writing is straightforward yet densely layered with philosophical, cinematic, and cultural references. His prose strikes a delicate balance between humor and disillusionment, satire and introspection. The science fiction he envisions doesn’t unfold in distant galaxies or pristine futures, but in a present warped by ambition, nostalgia, and absurdity.

Calien is a vital work in the context of contemporary Colombian science fiction. It doesn’t attempt to replicate Anglo-American genre norms, but instead forges its own voice —grounded in local realities and critical of global narratives. Its true power lies in the way it reimagines Cali —and by extension, Colombia— as a space for the fantastic, the ethical, and the alien.

The story is also available as part of the anthology "9 Fantastic Monsters".

Styncat

Genesis 88

La Parte Ausente

La Parte Ausente is about Chockler and his quest to find a man dead or alive, in a world on the brink of collapse.

The shooting lasted 5 weeks, almost everything in the cold and dark winter night.

We used the Red Epic camera because the DOP asked us for that one.

The budget of the film was about 400 thousand dollars. The resources were both public and private.

Black

Survivors

Watch shortfilm:

Nova

Now Ezequiel Romero, one of the directors, tells us about his movie "Nova":

Nova was a kind of experiment —it was shot in just 24 hours, and all the dialogue was improvised. I had this idea of a world that first celebrates beauty and then slowly dies as the light from a distant supernova reaches it. To film an entire hour of footage in a single day, we split the crew into two teams, each following one of the main characters. We used Canon 5D cameras simply because they were cheap and readily available.

The 2nd Horseman

As an ultra fan of scifi and action movies, the peruvian director Arthur Cross felt a natural need to create something that combined those two genres, despite the fact that neither of them were often explored in his own country.

Using independent film making techniques and resources such as the popular Canon 5D Mk2 and Mk3, a wheelchair for a dolly and applying lots and lots of post production wizardry, The 2nd Horseman production team strives to optimize resources to crank out the best production value despite the inherent adversity of working a project of this kind.

It could be said that there is a bright future ahead for indies, and as science fiction becomes science fact, we look forward to the new film-making, post production and network technologies that will even expand our horizons even more.

Rosario necesita héroes

An astral war.

Proxima

Now Carlos Atanes tells us about his movie "Proxima":

Watch Made in PROXIMA: Underground science fiction:

Martin Mosca

Now Mariano Cattaneo tells us about his webseries "Martin Mosca":

|

| Behind-the-scenes: Martin Mosca's house |

La furia de MacKenzie

Zohe

Justice Woman

El Sol

Now Ayar Blasco tell us about his movie "El Sol":

La maquina que escupe monstruos y la chica de mis sueños

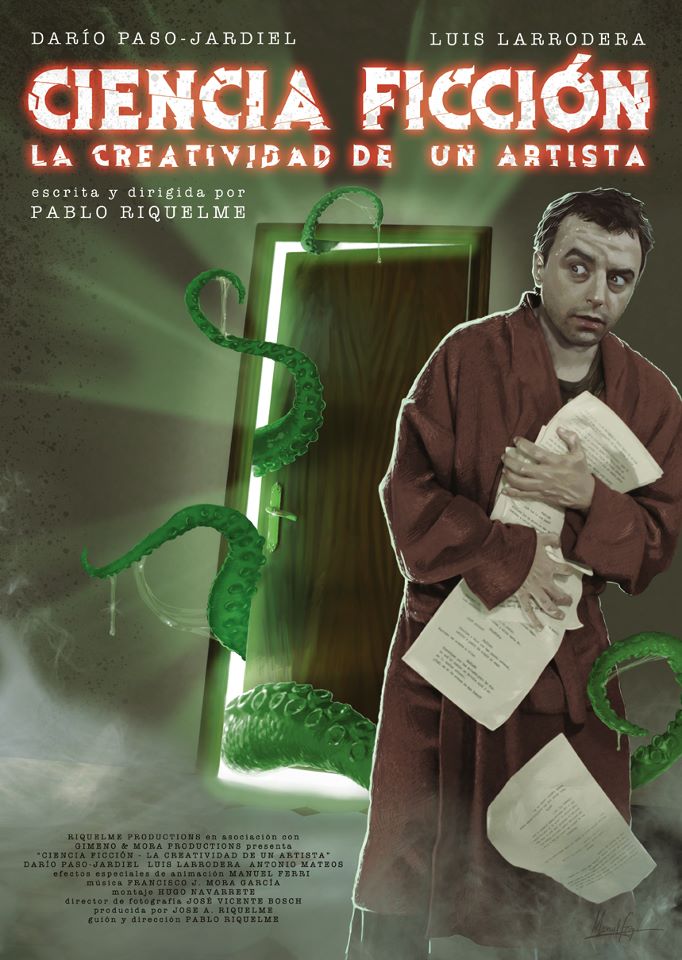

Ciencia Ficción: La creatividad de un artista

Los Cuchillos

Gen Mishima

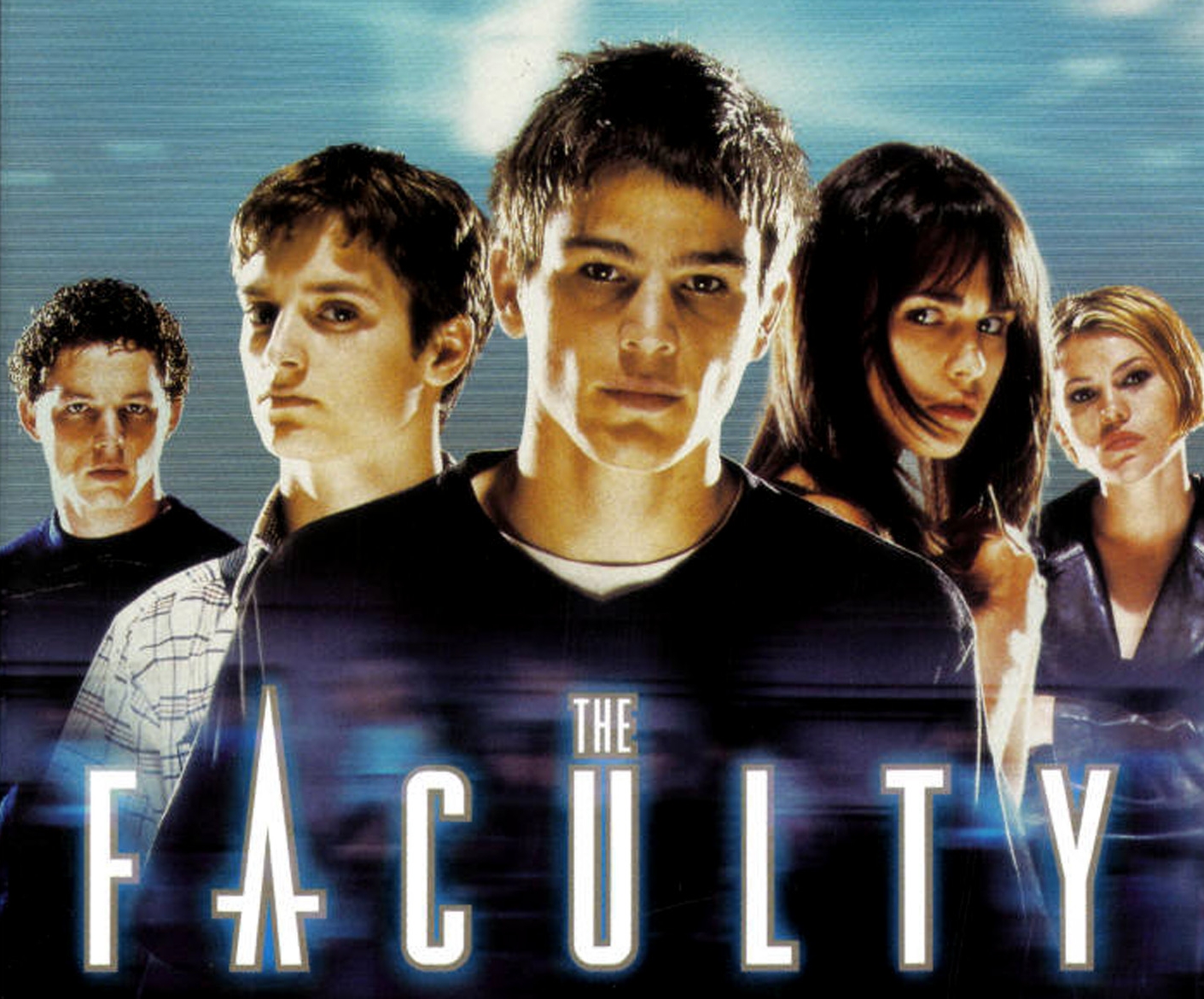

The Adventures of Shark Boy and Lava Girl in 3D

Other film of Robert Rodriguez:

Viaje a Marte

Mate on Mars.

Watch shortfilm:

Kaliman